The Problem with Iranian Cinema

Iranian cinema occupies a peculiar place in the global imagination. When Western audiences speak of Iranian film, they usually mean a handful of titles that have been screened at Cannes, Berlin, or the Oscars. These are films framed as humanist windows into a closed society, works that are praised precisely because they appear to lift the veil on an otherwise unknowable culture. Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) is perhaps the paradigmatic example: a middle-class couple at odds, a child caught in the middle, religion exerting quiet but forceful pressure on modern life. The West lauded it as a universal story, proof that beneath headscarves and sanctions, Iranians wrestle with the same moral questions as anyone else.

Yet there is a paradox here. The Iranian cinema that Western festivals elevate is rarely the cinema most alive in Tehran, Isfahan, or Shiraz. What travels abroad is carefully curated, sometimes even designed, for the foreign gaze. Films that resist Orientalist framings, films that show Iranians not as tragic, oppressed, or exotically pious but as cosmopolitan, joyful, and unremarkably human, remain largely unseen outside the country. This imbalance matters, because cinema does not simply entertain; it structures perception. What the West sees of Iran on screen becomes what it thinks Iran is.

The question is not whether these films are good. Many are. The question is why these particular films circulate, while others vanish into invisibility. And the answer lies in a colonial lens that has never been fully dismantled.

Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) argued that Western representations of the East have always functioned as a mirror. The Orient is imagined as sensual, backward, irrational, and trapped in history so that the West can see itself as rational, modern, and progressive. Cinema, with its capacity to project worlds, has been one of Orientalism’s most effective tools.

Iran, with its complex blend of Islamic tradition and modern intellectualism, has long unsettled Western categories. To resolve this anxiety, Western festivals and critics reward Iranian films that reproduce familiar binaries: piety versus secularism, tradition versus modernity, male authority versus female repression. These are not neutral frames. They reassure Western audiences that Iran is fundamentally other, a society perpetually lagging behind.

Social psychology explains part of this mechanism. Confirmation bias makes audiences seek films that affirm their pre-existing views. Selective exposure theory shows how people avoid material that challenges their assumptions. The Western audience, primed by decades of media coverage that casts Iran as a threat, gravitates toward Iranian films that confirm that narrative, even when disguised as universal humanism. The cinema that wins prizes is therefore often the cinema that fits the colonial script.

And here lies the American irony. The United States, a nation with less than three centuries of history, positions itself as arbiter of civilisation while judging a culture that has produced poetry, architecture, and visual art for over a thousand years. Iran had libraries, observatories, and universities before America existed. Yet through the Hollywood-centric lens, Iran becomes a perpetual pupil, only deemed legible when it presents its dysfunctions for Western inspection.

The Academy Awards’ International Feature category is the most visible arena for this process. It offers one slot per nation, which means the chosen film does not just represent a director but an entire culture. For Iran, the films that have reached this stage, Children of Heaven (1997), A Separation (2011), The Salesman (2016), are celebrated for their tender portrayals of ordinary life under strain. But notice the pattern: they all highlight division, repression, or entrapment. They are humane, but they are also circumscribed.

This is what Homi Bhabha would call containment. The foreign film slot allows America to congratulate itself for cultural openness while maintaining control over which versions of foreignness are acceptable. Iran becomes visible only in ways that align with American geopolitical interests: divided, struggling, in need of sympathy but never of admiration.

The Oscars’ soft power should not be underestimated. To win is to enter the global canon. To lose, or never to be selected, is to remain invisible. Thus America exports not just its films but its frameworks, shaping global understanding of entire nations through what it chooses to reward. Iran is not alone in this. Palestine, Afghanistan, and even Japan have been subjected to similar narrative pruning. But given America’s fraught relationship with Iran since 1979, the case is especially stark.

The Iranian films that rarely leave Iran tell a different story. They show middle classes negotiating globalisation, intellectuals debating philosophy, women not only oppressed but also powerful, witty, and cosmopolitan. These films exist, but they are dismissed by Western distributors as “not authentic.” Authenticity, in the colonial lexicon, means suffering.

Cultural theory calls this othering. The West validates its self-image by demanding portrayals of Iranian life that emphasise dysfunction or repression. The joy of everyday Iranian existence, family celebrations, architectural modernism, technological innovation, is excluded from the global cinematic record.

Consider how quickly Western audiences embraced Iranian films about silenced women, yet ignored Iranian women who have directed films themselves with subtlety and strength. The demand is not for Iranian voices, but for Iranian suffering performed in a way that Western audiences can applaud. This is voyeurism disguised as solidarity.

There is another paradox. Even as the West filters which Iranian stories are visible, it quietly absorbs Iranian cinematic techniques into its own canon. Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990) blurred documentary and fiction in ways that influenced Jim Jarmusch and Richard Linklater. His Taste of Cherry (1997) pioneered long takes and open endings that reappeared in Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Turkish dramas and even in American indie cinema.

Iranian directors developed a grammar of minimalism, ambiguity, and formal experimentation that Western filmmakers freely borrow, often without acknowledgement. The visual culture of Iran circulates, stripped of context, while the society that produced it remains caricatured as backward. This is cultural appropriation by invisibility.

The result is a cinema where Western auteurs gain prestige for techniques pioneered in Tehran, while Iranian filmmakers are granted visibility only when they confirm stereotypes about their country. It is a double erasure: of cultural credit and of cultural complexity.

Why does this dynamic persist? Social psychology points to system justification theory: people are motivated to see the existing social order as fair and legitimate, even when it is not. For Western audiences, consuming Iranian films that align with Orientalist expectations reassures them that their worldview is accurate. Iran is shown as divided, regressive, or authoritarian, which justifies sanctions, drone strikes, and diplomatic isolation.

Moral licensing plays a role as well. Watching films about “oppressed Iranian women” allows Western viewers to feel enlightened, even progressive, while ignoring their own governments’ role in destabilising the region. The act of consumption becomes a substitute for political engagement. Viewers can sympathise with Iranian characters on screen while supporting policies that harm Iranians off screen.

America exemplifies this contradiction. The same country that applauds A Separation at the Oscars has spent decades strangling the Iranian economy through sanctions, undermining ordinary people’s lives. It bombs Iraq in the name of freedom, then pats itself on the back for watching Iranian films about suffering. The hypocrisy is staggering. Cultural openness becomes a mask for political aggression.

This complicity extends beyond Iran. Western audiences consume Palestinian cinema about dispossession, Afghan cinema about war, Indian cinema about poverty, all the while reinforcing the systems that perpetuate those conditions. The films are not lies, but the framework in which they are received is profoundly dishonest.

What would it mean to see Iranian cinema without the colonial filter? It would mean films about art, joy, and cosmopolitan life gaining the same visibility as films about repression. It would mean acknowledging that Iranian intellectual life is not a deviation but a central strand in world culture.

Iranian cinema could show the endurance of Persian poetry in everyday speech, the sophistication of its architecture, the humour of its urban youth. Protest on screen need not always be framed as tragedy. It can also be framed as resilience, creativity, and defiance.

For this to happen, however, Western audiences must change their viewing habits. It is not enough for Iranian filmmakers to resist pandering; distributors, critics, and viewers must resist consuming Iranian cinema as Orientalist spectacle. To treat Iranian cinema as art rather than anthropology would be a first step.

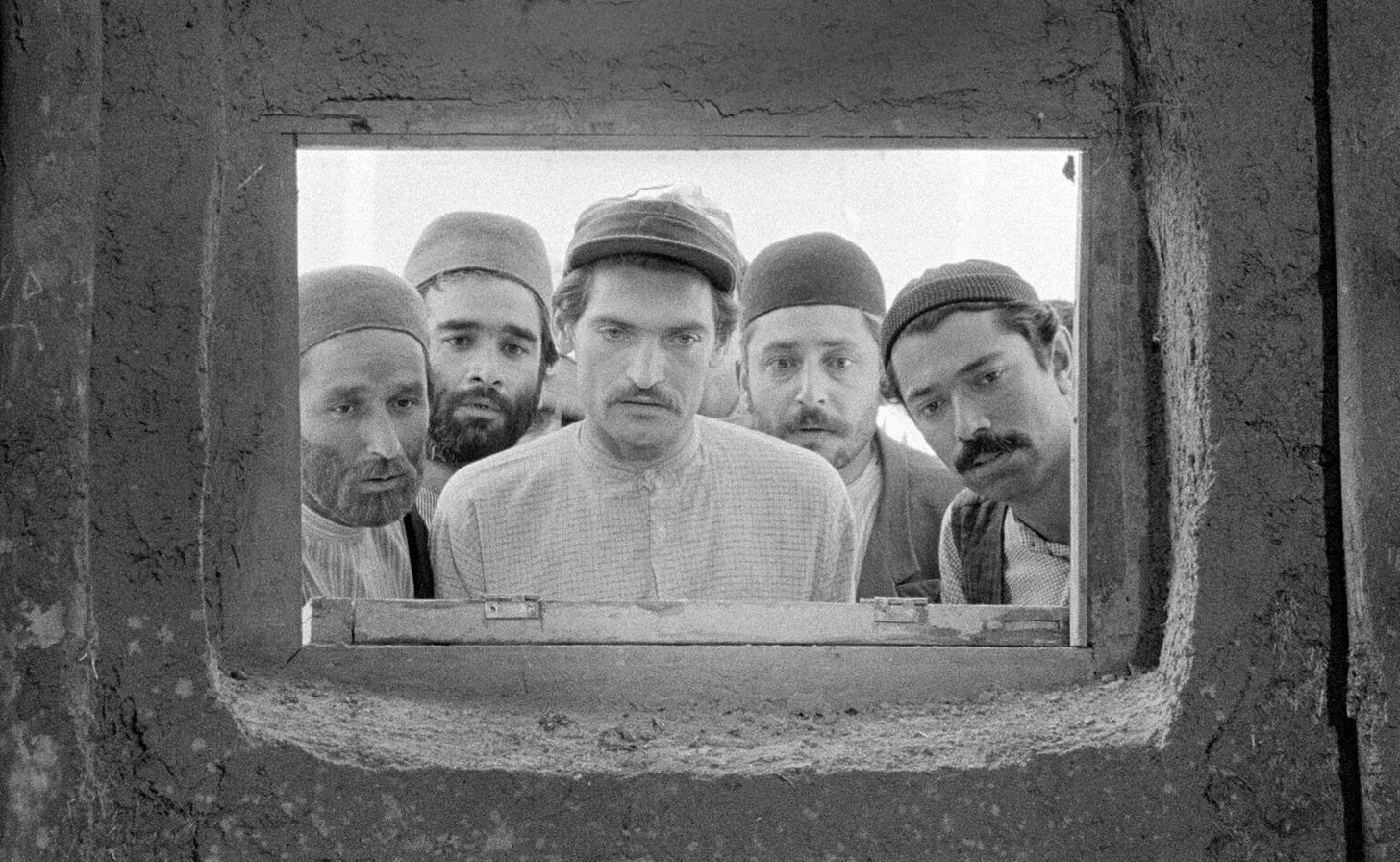

Iranian cinema in the West is like a shop window. We see only what distributors place there, and the selection is curated to sell a particular narrative. What lies behind the glass is richer, stranger, and more complex than most audiences ever realise.

The problem with Iranian cinema is not the films themselves but the structures through which they are consumed. Western audiences mistake the part for the whole, then congratulate themselves for their cultural sophistication. America in particular exemplifies this delusion: a young nation that judges an ancient civilisation, rewarding only those images that fit its geopolitical self-image.

Cinema can do better. Viewers can do better. If we look beyond the Oscarised Iran, we may rediscover a cinema that not only resists but also teaches, innovates, and rehumanises. Iran does not need Western validation to prove its cultural worth. But the West, if it wishes to see itself clearly, needs Iranian cinema, unfiltered, uncontained, and free.

References

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. Routledge.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18.

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33(1), 1–27.

Monahan, T. (2006). Counter-surveillance as political intervention? Social Semiotics, 16(4), 515–534.

If this essay resonated, share it with someone who only knows Iran through the Oscars. Subscribe to Rialto 5: 15 for more essays on cinema, culture, and the hidden architectures of how we watch. Your support builds the canon we deserve.